OK, OK, OK. I know. I went to Vietnam and didn't write about. And then I went to Hawaii, and didn't mention it. I promise to write about these things...later.

Until then, this is too good not to post.

---

China: Tallest Man to the Rescue of 2 Dolphins

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS (NYT)

The long arms of Bao Xishun, the world’s tallest man, reached in and saved two dolphins by pulling plastic from their stomachs, state news media and an aquarium official said. The dolphins got sick after eating plastic that fell into their aquarium pool in Liaoning Province. Attempts to remove the plastic surgically failed, The China Daily reported, and veterinarians decided to ask for help from Mr. Bao, a 7-foot-9 herdsman from Inner Mongolia with 41.7-inch arms. “He did it successfully yesterday,” said Chen Lujun, the manager at Royal Jidi Ocean World. “The two dolphins are in very good condition now.” Mr. Bao, 54, was declared the world’s tallest living man by Guinness World Records last year.

Sunday, December 17, 2006

China must be the best place in the world to be a Eurasian. Of all the stereotypes fostered in China--Americans are rich, French people are romantic, Russians have big noses, to give a few--none compare to what is nearly universally said about mixed-blooded babies: They are clever AND beautiful. CLEVER and BEAUTIFUL. Any Beijing taxi driver will tell you this is a fact. Even Michael, my similarily mixed-blooded former flatmate, was once told by one of his students, "It is scientifically proven that hun xue'er (Chinese for mixed blood) are smarter than ordinary people!" Of course, both Michael and I knew this all along...

So, today I had to call the States to sort out an issue with my credit card bill. For reasons unknown to me, my call was transferred to a woman who spoke very good English, but with a distinct Chinese accent. We chatted a bit and once my payment situation was resolved, I asked her if she was Chinese. She told me she was. I told her I was in China and that my mother was Chinese and she said, "But you don't sound like a Chinese." I explained that I was born and raised in the States, but now I live in China, and that my father is an American. "I'm a hun xue'er," I declared. "Oh! Hun xue'er!," she exclaimed over the phone, from somewhere in the U.S. to my home office in Beijing, "you must be very beautiful!"

Obviously, my reputation precedes me.

So, today I had to call the States to sort out an issue with my credit card bill. For reasons unknown to me, my call was transferred to a woman who spoke very good English, but with a distinct Chinese accent. We chatted a bit and once my payment situation was resolved, I asked her if she was Chinese. She told me she was. I told her I was in China and that my mother was Chinese and she said, "But you don't sound like a Chinese." I explained that I was born and raised in the States, but now I live in China, and that my father is an American. "I'm a hun xue'er," I declared. "Oh! Hun xue'er!," she exclaimed over the phone, from somewhere in the U.S. to my home office in Beijing, "you must be very beautiful!"

Obviously, my reputation precedes me.

Friday, November 10, 2006

My mother was just in town. She came to China for business, and spent a few days in Beijing, at the end of her trip. I met up with her and some of her colleagues, and the question I got asked most often was, "How is your life in China?"

This question came to me from Americans, and one Czech, who were rounding up a rather long, poorly organized, and sometimes uncomfortable trip. It was a very "Chinese" trip, from what I gathered, and even my mother, who came along to serve as interpreter, was fed up with China, at the end. (**Note: My mother is Chinese, and speaks the language as her first, however she has never lived on the mainland, and no longer has close family ties to it. Aside from me, of course).

Despite sympathizing with the woes of these travellers, all I could say, in candor, without the slightest bit of exaggeration, was, "My life is excellent." And it is.

Work is good. I have plenty of friends. There is lots to do, and I am never bored. NEVER BORED. Which is something I would never, ever say, about being in Kona, or Los Angeles. (I was rarely bored in Boston, so that's why it's not on the list.)

What people who haven't spent time significant time in China--including the Chinese in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the States, or wherever--don't understand is that you cannot expect it to be anything more than what it is: a massive, diverse, developing country that is densely populated with a people that are grappling with trying to embrace to their own culture, equipped only with an understanding of the world borne out of more than 50 years of government-controlled information, in the face of lightning-speed economic and technological advancements resulting from communication prying in from the outside. While a 7-year-old Beijinger might easily be able to attach a photo to an e-mail and send it off in English, it wouldn't be fair to assume that the salesgirl at the market, who can speak basic English, French, Russian and Korean will be able to read a map, or even tell you which way is North. Kids at concerts have spiked, dyed hair and wear chains, but precious few have ever heard of Sid Vicious, and people apologize when they bump into you in the mosh pit. Rich kids can go overseas for university, but most would starve to death lying next to a frying pan and eggs. In the provincial areas, people who never got past grammar school lead villages, and in the cities, parents who have devoted their lives to their only child's education go to job fairs on behalf of them when they are unable or unambitious enough to find jobs themselves.

To sit comfortably, and to see all this happen, is never boring. There is a "New China" Zeitgeist that can only truly be appreciated here on the ground, and only after one gets past the spitting, the food poisoning, the incompetence of the average person, the disorganization and the general dysfunction of the place.

My friends back home just don't get how I could possibly give up Hawaii for China, and I just can't see why any young person would ever want to live in America. Despite the chaos, corruption, mismanagement and backward thinking, China's economic growth averages nearly 10% per annum. TEN PERCENT! America knows well the importance of China to the global economy, but only now is the concept of it as a political power appearing in the mainstream. France gets it, Russia gets it, Africa seems to dig it, Japan is always on the alert, but the average American is only now starting to consider it. Imagine what people will think when, or if, China manages to get really its shit together.

Tom Friedman of the New York Times is in China now, and I will go to see him talk at one of the local bookstores tomorrow. This is what he wrote yesterday. He gets it too.

---

China: Scapegoat or Sputnik

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

November 10, 2006

Shanghai

As I was saying, Mr. Rove, Americans aren’t as stupid as you think.

Now that we’ve settled that, and now that we’ve had an election that clarified which country is most important in shaping U.S. politics in 2006 — Iraq — I’ve come to visit the country that’s most likely to shape U.S. politics in 2008: China.

The civil war in the Republican Party, which you are about to see, will be all about Iraq — whom to blame and how to withdraw before the issue wipes out more Republican candidates in 2008. But the coming civil war among the Democrats will be all about China.

I still believe that when the history of this era is written, the trend that historians will cite as the most significant will not be 9/11 and the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. It will be the rise of China and India. How the world accommodates itself to these rising powers, and how America manages the economic opportunities and challenges they pose, is still the most important global trend to watch.

It really hits you when you see the supersize buildings sprouting in Shanghai, or when you look at the world through non-American eyes. Kishore Mahbubani, the dean of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, told me the other day that Asia right now “is the most optimistic place in the world.” More people have come out of poverty faster there — particularly in India and China — than at any time in the history of the world, and as a result, he notes, more people in Asia than anywhere else in the world today “wake up every morning sure that tomorrow is going to be better than yesterday.”

But one person’s optimism can be another person’s flat wages. And that is why the Democrats and China are almost certain to butt heads. The Bush team’s focus on Iraq and terrorism, coupled with the Democrats’ lack of control over either house of Congress, has kept China-U.S. relations largely out of the headlines and on a relatively even keel during the Bush II years.

But two things will change that. One is the Democrats’ return to control of both the House and Senate — powered by politicians like Nancy Pelosi, who has long taken a hard line vis-à-vis China on both economics and human rights, and Sherrod Brown, the newly elected senator from Ohio, who comes to D.C. with strong protectionist leanings from a state that has lost thousands of manufacturing jobs to Asia.

The other is the mood reflected in a Nov. 2 analysis in The Financial Times, headlined: “Anxious Middle: Why Ordinary Americans Have Missed Out on the Benefits of Growth.”

Technology and globalization are flattening the global economic playing field today, enabling many more developing nations to compete for white-collar and blue-collar jobs once reserved for the developed world. This is one reason why growth in wages for the average U.S. worker has not been keeping pace with our growth in productivity and G.D.P.

“Economists call this phenomenon median wage stagnation,” noted The Financial Times. “Median measures give the best picture of what is happening to the middle class because, unlike mean or average wages, median wages are not pulled upwards by rapid gains at the top. As the joke goes: Bill Gates walks into a bar and, on average, everyone there becomes a millionaire. But the median does not change.”

Many Americans lately have started to get that joke, and it is one reason that with this new Democrat-led Congress we are likely to see a surge in protectionist legislation, more Wal-Mart bashing, a slowdown in free-trade expansion and increased calls for punitive actions if China doesn’t reduce its trade surplus — which surged to a record in October.

China, in other words, is inevitably going to move back to the center of U.S. politics, because it crystallizes the economic challenges faced by U.S. workers in the 21st century. The big question for me is, how will President Bush and the Democratic Congress use China: as a scapegoat or a Sputnik?

Will they use it as an excuse to avoid doing the hard things, because it’s all just China’s fault, or as an excuse to rally the country — as we did after the Soviets leapt ahead of us in the space race and launched Sputnik — to make the kind of comprehensive changes in health care, portability of pensions, entitlements and lifelong learning to give America’s middle class the best tools possible to thrive? A lot of history is going to turn on that answer, because if people don’t feel they have the tools or skills to thrive in a world without walls, the pressure to put up walls, especially against China, will steadily mount.

This question came to me from Americans, and one Czech, who were rounding up a rather long, poorly organized, and sometimes uncomfortable trip. It was a very "Chinese" trip, from what I gathered, and even my mother, who came along to serve as interpreter, was fed up with China, at the end. (**Note: My mother is Chinese, and speaks the language as her first, however she has never lived on the mainland, and no longer has close family ties to it. Aside from me, of course).

Despite sympathizing with the woes of these travellers, all I could say, in candor, without the slightest bit of exaggeration, was, "My life is excellent." And it is.

Work is good. I have plenty of friends. There is lots to do, and I am never bored. NEVER BORED. Which is something I would never, ever say, about being in Kona, or Los Angeles. (I was rarely bored in Boston, so that's why it's not on the list.)

What people who haven't spent time significant time in China--including the Chinese in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the States, or wherever--don't understand is that you cannot expect it to be anything more than what it is: a massive, diverse, developing country that is densely populated with a people that are grappling with trying to embrace to their own culture, equipped only with an understanding of the world borne out of more than 50 years of government-controlled information, in the face of lightning-speed economic and technological advancements resulting from communication prying in from the outside. While a 7-year-old Beijinger might easily be able to attach a photo to an e-mail and send it off in English, it wouldn't be fair to assume that the salesgirl at the market, who can speak basic English, French, Russian and Korean will be able to read a map, or even tell you which way is North. Kids at concerts have spiked, dyed hair and wear chains, but precious few have ever heard of Sid Vicious, and people apologize when they bump into you in the mosh pit. Rich kids can go overseas for university, but most would starve to death lying next to a frying pan and eggs. In the provincial areas, people who never got past grammar school lead villages, and in the cities, parents who have devoted their lives to their only child's education go to job fairs on behalf of them when they are unable or unambitious enough to find jobs themselves.

To sit comfortably, and to see all this happen, is never boring. There is a "New China" Zeitgeist that can only truly be appreciated here on the ground, and only after one gets past the spitting, the food poisoning, the incompetence of the average person, the disorganization and the general dysfunction of the place.

My friends back home just don't get how I could possibly give up Hawaii for China, and I just can't see why any young person would ever want to live in America. Despite the chaos, corruption, mismanagement and backward thinking, China's economic growth averages nearly 10% per annum. TEN PERCENT! America knows well the importance of China to the global economy, but only now is the concept of it as a political power appearing in the mainstream. France gets it, Russia gets it, Africa seems to dig it, Japan is always on the alert, but the average American is only now starting to consider it. Imagine what people will think when, or if, China manages to get really its shit together.

Tom Friedman of the New York Times is in China now, and I will go to see him talk at one of the local bookstores tomorrow. This is what he wrote yesterday. He gets it too.

---

China: Scapegoat or Sputnik

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

November 10, 2006

Shanghai

As I was saying, Mr. Rove, Americans aren’t as stupid as you think.

Now that we’ve settled that, and now that we’ve had an election that clarified which country is most important in shaping U.S. politics in 2006 — Iraq — I’ve come to visit the country that’s most likely to shape U.S. politics in 2008: China.

The civil war in the Republican Party, which you are about to see, will be all about Iraq — whom to blame and how to withdraw before the issue wipes out more Republican candidates in 2008. But the coming civil war among the Democrats will be all about China.

I still believe that when the history of this era is written, the trend that historians will cite as the most significant will not be 9/11 and the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. It will be the rise of China and India. How the world accommodates itself to these rising powers, and how America manages the economic opportunities and challenges they pose, is still the most important global trend to watch.

It really hits you when you see the supersize buildings sprouting in Shanghai, or when you look at the world through non-American eyes. Kishore Mahbubani, the dean of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, told me the other day that Asia right now “is the most optimistic place in the world.” More people have come out of poverty faster there — particularly in India and China — than at any time in the history of the world, and as a result, he notes, more people in Asia than anywhere else in the world today “wake up every morning sure that tomorrow is going to be better than yesterday.”

But one person’s optimism can be another person’s flat wages. And that is why the Democrats and China are almost certain to butt heads. The Bush team’s focus on Iraq and terrorism, coupled with the Democrats’ lack of control over either house of Congress, has kept China-U.S. relations largely out of the headlines and on a relatively even keel during the Bush II years.

But two things will change that. One is the Democrats’ return to control of both the House and Senate — powered by politicians like Nancy Pelosi, who has long taken a hard line vis-à-vis China on both economics and human rights, and Sherrod Brown, the newly elected senator from Ohio, who comes to D.C. with strong protectionist leanings from a state that has lost thousands of manufacturing jobs to Asia.

The other is the mood reflected in a Nov. 2 analysis in The Financial Times, headlined: “Anxious Middle: Why Ordinary Americans Have Missed Out on the Benefits of Growth.”

Technology and globalization are flattening the global economic playing field today, enabling many more developing nations to compete for white-collar and blue-collar jobs once reserved for the developed world. This is one reason why growth in wages for the average U.S. worker has not been keeping pace with our growth in productivity and G.D.P.

“Economists call this phenomenon median wage stagnation,” noted The Financial Times. “Median measures give the best picture of what is happening to the middle class because, unlike mean or average wages, median wages are not pulled upwards by rapid gains at the top. As the joke goes: Bill Gates walks into a bar and, on average, everyone there becomes a millionaire. But the median does not change.”

Many Americans lately have started to get that joke, and it is one reason that with this new Democrat-led Congress we are likely to see a surge in protectionist legislation, more Wal-Mart bashing, a slowdown in free-trade expansion and increased calls for punitive actions if China doesn’t reduce its trade surplus — which surged to a record in October.

China, in other words, is inevitably going to move back to the center of U.S. politics, because it crystallizes the economic challenges faced by U.S. workers in the 21st century. The big question for me is, how will President Bush and the Democratic Congress use China: as a scapegoat or a Sputnik?

Will they use it as an excuse to avoid doing the hard things, because it’s all just China’s fault, or as an excuse to rally the country — as we did after the Soviets leapt ahead of us in the space race and launched Sputnik — to make the kind of comprehensive changes in health care, portability of pensions, entitlements and lifelong learning to give America’s middle class the best tools possible to thrive? A lot of history is going to turn on that answer, because if people don’t feel they have the tools or skills to thrive in a world without walls, the pressure to put up walls, especially against China, will steadily mount.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Three things happened yesterday that have renewed my faith in humanity. Just a little. (Which is a lot.)

Here they are:

1. The Democrats got control of the Senate and the House! and 1a., on a related note, Rummy stepped down. Christ, he must have a lot of skeletons in his closet!

Now, as I have mentioned before, I no longer consider myself a Democrat. However, the United States government is a two party system, and with that in mind, I'd rather have the Dems in power than the GOP. A colleague of mine, an ill-informed-on-this-topic non-American said, "yeah, but it's not like anything will change just because the party in control has changed", and this irritated me. For sure, I recognize that our two parties are more similar than differing parties in other countries, but to say it doesn't matter is simply not true. Had Clinton, or Kerry, or Gore, or say, even John McCain, been in charge when the Twin Towers went down, I confidently believe that the fiasco which is now Iraq, would not have gone down the way it did. That's not to say we wouldn't have gotten into conflict, but with little question in my mind, Clinton would have been a lot smoother about the whole thing, and he probably would have been a hell of a lot quicker to nip the Gitmo situation in the bud. Conspiracy theorists might even argue that 9/11 wouldn't have happened at all, if Bush were never elected...

Also, as I believe that this change in power will result in a withdrawal from Iraq, sooner than later, and possibly before Bush ends his term, I forsee a shift policy focus, from foreign to domestic. This would be good for America, and it also means that Hilary, who may in fact, be on the Democratic ticket for 2008, could stand a chance of winning. (I simply don't believe America in war would ever elect its first woman president.) Not that I love Hilary, but I do think it would be interesting if she were elected, especially given that Germany has Merkel, and Royal may very well take power in France.

2. I found out that Britney Spears has filed for divorce. OK, so this is not high up on the list of things that matter in the world, but shit, even 24-year-old popstar Britney has enough sense to see what the rest of the media sees and get rid of her useless, and not really very good-looking leech of a husband.

3. I lost my mobile phone in a taxi AND it was returned to me. Every morning, I have to take a cab across town to get to work. Yesterday, I had it with me in the car, but not in my office, so when I got home, I called the number on the receipt (ALWAYS, ALWAYS keep the receipt!). Through my broken Chinese, I conveyed that I left my phone in the cab whose license number was on the slip. The woman at the dispatch station called the driver, he confirmed that I did, in fact, leave the phone in his car, and as luck would have it, he was in my neighborhood. He brought it to me ten minutes later, and when I offered him the cab fare to get to me, he refused. I had brought down a bottle of Samuel Adams, thinking he'd probably be near the end of his shift--which he was--and might like a cold one, and after a half-hearted refusal, he accepted the beer. (This was after I explained, "Shi mei guo de pi jiu! Ba shi dun de pi jiu! Hen hao he le! It is American beer! From Boston! It's excellent!")

So, at the end of the day, not all people are stupid bastards and life is pretty good!

Here they are:

1. The Democrats got control of the Senate and the House! and 1a., on a related note, Rummy stepped down. Christ, he must have a lot of skeletons in his closet!

Now, as I have mentioned before, I no longer consider myself a Democrat. However, the United States government is a two party system, and with that in mind, I'd rather have the Dems in power than the GOP. A colleague of mine, an ill-informed-on-this-topic non-American said, "yeah, but it's not like anything will change just because the party in control has changed", and this irritated me. For sure, I recognize that our two parties are more similar than differing parties in other countries, but to say it doesn't matter is simply not true. Had Clinton, or Kerry, or Gore, or say, even John McCain, been in charge when the Twin Towers went down, I confidently believe that the fiasco which is now Iraq, would not have gone down the way it did. That's not to say we wouldn't have gotten into conflict, but with little question in my mind, Clinton would have been a lot smoother about the whole thing, and he probably would have been a hell of a lot quicker to nip the Gitmo situation in the bud. Conspiracy theorists might even argue that 9/11 wouldn't have happened at all, if Bush were never elected...

Also, as I believe that this change in power will result in a withdrawal from Iraq, sooner than later, and possibly before Bush ends his term, I forsee a shift policy focus, from foreign to domestic. This would be good for America, and it also means that Hilary, who may in fact, be on the Democratic ticket for 2008, could stand a chance of winning. (I simply don't believe America in war would ever elect its first woman president.) Not that I love Hilary, but I do think it would be interesting if she were elected, especially given that Germany has Merkel, and Royal may very well take power in France.

2. I found out that Britney Spears has filed for divorce. OK, so this is not high up on the list of things that matter in the world, but shit, even 24-year-old popstar Britney has enough sense to see what the rest of the media sees and get rid of her useless, and not really very good-looking leech of a husband.

3. I lost my mobile phone in a taxi AND it was returned to me. Every morning, I have to take a cab across town to get to work. Yesterday, I had it with me in the car, but not in my office, so when I got home, I called the number on the receipt (ALWAYS, ALWAYS keep the receipt!). Through my broken Chinese, I conveyed that I left my phone in the cab whose license number was on the slip. The woman at the dispatch station called the driver, he confirmed that I did, in fact, leave the phone in his car, and as luck would have it, he was in my neighborhood. He brought it to me ten minutes later, and when I offered him the cab fare to get to me, he refused. I had brought down a bottle of Samuel Adams, thinking he'd probably be near the end of his shift--which he was--and might like a cold one, and after a half-hearted refusal, he accepted the beer. (This was after I explained, "Shi mei guo de pi jiu! Ba shi dun de pi jiu! Hen hao he le! It is American beer! From Boston! It's excellent!")

So, at the end of the day, not all people are stupid bastards and life is pretty good!

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Friday, November 03, 2006

Here's another one... God bless the thinking American, for I know they do exist, if only in small and scattered quantities...

Insulting Our Troops, and Our Intelligence

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

November 3, 2006

George Bush, Dick Cheney and Don Rumsfeld think you’re stupid. Yes, they do.

They think they can take a mangled quip about President Bush and Iraq by John Kerry — a man who is not even running for office but who, unlike Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney, never ran away from combat service — and get you to vote against all Democrats in this election.

Every time you hear Mr. Bush or Mr. Cheney lash out against Mr. Kerry, I hope you will say to yourself, “They must think I’m stupid.” Because they surely do.

They think that they can get you to overlook all of the Bush team’s real and deadly insults to the U.S. military over the past six years by hyping and exaggerating Mr. Kerry’s mangled gibe at the president.

What could possibly be more injurious and insulting to the U.S. military than to send it into combat in Iraq without enough men — to launch an invasion of a foreign country not by the Powell Doctrine of overwhelming force, but by the Rumsfeld Doctrine of just enough troops to lose? What could be a bigger insult than that?

What could possibly be more injurious and insulting to our men and women in uniform than sending them off to war without the proper equipment, so that some soldiers in the field were left to buy their own body armor and to retrofit their own jeeps with scrap metal so that roadside bombs in Iraq would only maim them for life and not kill them? And what could be more injurious and insulting than Don Rumsfeld’s response to criticism that he sent our troops off in haste and unprepared: Hey, you go to war with the army you’ve got — get over it.

What could possibly be more injurious and insulting to our men and women in uniform than to send them off to war in Iraq without any coherent postwar plan for political reconstruction there, so that the U.S. military has had to assume not only security responsibilities for all of Iraq but the political rebuilding as well? The Bush team has created a veritable library of military histories — from “Cobra II” to “Fiasco” to “State of Denial” — all of which contain the same damning conclusion offered by the very soldiers and officers who fought this war: This administration never had a plan for the morning after, and we’ve been making it up — and paying the price — ever since.

And what could possibly be more injurious and insulting to our men and women in Iraq than to send them off to war and then go out and finance the very people they’re fighting against with our gluttonous consumption of oil? Sure, George Bush told us we’re addicted to oil, but he has not done one single significant thing — demanded higher mileage standards from Detroit, imposed a gasoline tax or even used the bully pulpit of the White House to drive conservation — to end that addiction. So we continue to finance the U.S. military with our tax dollars, while we finance Iran, Syria, Wahhabi mosques and Al Qaeda madrassas with our energy purchases.

Everyone says that Karl Rove is a genius. Yeah, right. So are cigarette companies. They get you to buy cigarettes even though we know they cause cancer. That is the kind of genius Karl Rove is. He is not a man who has designed a strategy to reunite our country around an agenda of renewal for the 21st century — to bring out the best in us. His “genius” is taking some irrelevant aside by John Kerry and twisting it to bring out the worst in us, so you will ignore the mess that the Bush team has visited on this country.

And Karl Rove has succeeded at that in the past because he was sure that he could sell just enough Bush cigarettes, even though people knew they caused cancer. Please, please, for our country’s health, prove him wrong this time.

Let Karl know that you’re not stupid. Let him know that you know that the most patriotic thing to do in this election is to vote against an administration that has — through sheer incompetence — brought us to a point in Iraq that was not inevitable but is now unwinnable.

Let Karl know that you think this is a critical election, because you know as a citizen that if the Bush team can behave with the level of deadly incompetence it has exhibited in Iraq — and then get away with it by holding on to the House and the Senate — it means our country has become a banana republic. It means our democracy is in tatters because it is so gerrymandered, so polluted by money, and so divided by professional political hacks that we can no longer hold the ruling party to account.

It means we’re as stupid as Karl thinks we are.

I, for one, don’t think we’re that stupid. Next Tuesday we’ll see.

Insulting Our Troops, and Our Intelligence

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

November 3, 2006

George Bush, Dick Cheney and Don Rumsfeld think you’re stupid. Yes, they do.

They think they can take a mangled quip about President Bush and Iraq by John Kerry — a man who is not even running for office but who, unlike Mr. Bush and Mr. Cheney, never ran away from combat service — and get you to vote against all Democrats in this election.

Every time you hear Mr. Bush or Mr. Cheney lash out against Mr. Kerry, I hope you will say to yourself, “They must think I’m stupid.” Because they surely do.

They think that they can get you to overlook all of the Bush team’s real and deadly insults to the U.S. military over the past six years by hyping and exaggerating Mr. Kerry’s mangled gibe at the president.

What could possibly be more injurious and insulting to the U.S. military than to send it into combat in Iraq without enough men — to launch an invasion of a foreign country not by the Powell Doctrine of overwhelming force, but by the Rumsfeld Doctrine of just enough troops to lose? What could be a bigger insult than that?

What could possibly be more injurious and insulting to our men and women in uniform than sending them off to war without the proper equipment, so that some soldiers in the field were left to buy their own body armor and to retrofit their own jeeps with scrap metal so that roadside bombs in Iraq would only maim them for life and not kill them? And what could be more injurious and insulting than Don Rumsfeld’s response to criticism that he sent our troops off in haste and unprepared: Hey, you go to war with the army you’ve got — get over it.

What could possibly be more injurious and insulting to our men and women in uniform than to send them off to war in Iraq without any coherent postwar plan for political reconstruction there, so that the U.S. military has had to assume not only security responsibilities for all of Iraq but the political rebuilding as well? The Bush team has created a veritable library of military histories — from “Cobra II” to “Fiasco” to “State of Denial” — all of which contain the same damning conclusion offered by the very soldiers and officers who fought this war: This administration never had a plan for the morning after, and we’ve been making it up — and paying the price — ever since.

And what could possibly be more injurious and insulting to our men and women in Iraq than to send them off to war and then go out and finance the very people they’re fighting against with our gluttonous consumption of oil? Sure, George Bush told us we’re addicted to oil, but he has not done one single significant thing — demanded higher mileage standards from Detroit, imposed a gasoline tax or even used the bully pulpit of the White House to drive conservation — to end that addiction. So we continue to finance the U.S. military with our tax dollars, while we finance Iran, Syria, Wahhabi mosques and Al Qaeda madrassas with our energy purchases.

Everyone says that Karl Rove is a genius. Yeah, right. So are cigarette companies. They get you to buy cigarettes even though we know they cause cancer. That is the kind of genius Karl Rove is. He is not a man who has designed a strategy to reunite our country around an agenda of renewal for the 21st century — to bring out the best in us. His “genius” is taking some irrelevant aside by John Kerry and twisting it to bring out the worst in us, so you will ignore the mess that the Bush team has visited on this country.

And Karl Rove has succeeded at that in the past because he was sure that he could sell just enough Bush cigarettes, even though people knew they caused cancer. Please, please, for our country’s health, prove him wrong this time.

Let Karl know that you’re not stupid. Let him know that you know that the most patriotic thing to do in this election is to vote against an administration that has — through sheer incompetence — brought us to a point in Iraq that was not inevitable but is now unwinnable.

Let Karl know that you think this is a critical election, because you know as a citizen that if the Bush team can behave with the level of deadly incompetence it has exhibited in Iraq — and then get away with it by holding on to the House and the Senate — it means our country has become a banana republic. It means our democracy is in tatters because it is so gerrymandered, so polluted by money, and so divided by professional political hacks that we can no longer hold the ruling party to account.

It means we’re as stupid as Karl thinks we are.

I, for one, don’t think we’re that stupid. Next Tuesday we’ll see.

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Being a dedicated New York Times reader, I have subscribed to their extended member services. Part of this package includes being able to set up a list of topics that are most interesting to you, and then, when something involving one of those topics is published, an alert is sent to you e-mail address. Among my topics of interest are China, RMB revalution, South America and Cuba. (Not that I'm a communist, but rather an interested observer of transitional and/or planned economies.)

I got this headline in my inbox this morning, and far and away, it is the funniest I have read this year:

Though Frail, Castro Denies He’s Dead

By REUTERS

Published: October 29, 2006

HAVANA, Oct. 28 (Reuters) — Fidel Castro, looking thin and tired, appeared Saturday on television and defiantly dismissed rumors that he was dead, as images showed him walking, talking on the telephone and reading the day’s newspaper.

Mr. Castro said he was taking part in government decisions, following the news and making regular phone calls as he recovers from emergency intestinal surgery in late July.

“Now that our enemies have prematurely declared me dying or dead, I am happy to send my compatriots and friends around the world this short film material,” he said. “Now let’s see what they say. They will have to resurrect me.”

The last public image of him was released in mid-September, when he was shown in photos with world leaders at a summit meeting in Havana.

---

What can you say other than "Viva Fidel!"

I got this headline in my inbox this morning, and far and away, it is the funniest I have read this year:

Though Frail, Castro Denies He’s Dead

By REUTERS

Published: October 29, 2006

HAVANA, Oct. 28 (Reuters) — Fidel Castro, looking thin and tired, appeared Saturday on television and defiantly dismissed rumors that he was dead, as images showed him walking, talking on the telephone and reading the day’s newspaper.

Mr. Castro said he was taking part in government decisions, following the news and making regular phone calls as he recovers from emergency intestinal surgery in late July.

“Now that our enemies have prematurely declared me dying or dead, I am happy to send my compatriots and friends around the world this short film material,” he said. “Now let’s see what they say. They will have to resurrect me.”

The last public image of him was released in mid-September, when he was shown in photos with world leaders at a summit meeting in Havana.

---

What can you say other than "Viva Fidel!"

Sunday, October 08, 2006

OK. I take back all the things I said about French people being slow and me, an American, being punctual and efficient. The French are slow, and so am I! I did an interview last week, and it has taken me a week to complete! Putain. I am such a slacker.

But this interview was really something else. I don't think I can write terribly much about it here, as I am being paid to write about it for the magazine, but let me tell you just a bit about it. A friend of mine, while drunk at a party last year, told me about these Americans living on farm outside of Beijing who came to China to join the communist revolution. After many e-mails and phone calls, I found this woman. She was out in the city at a dinner event with Wen Jiabao when I called, but much to my surprise, she returned my call later that night. She asked me what I wanted and told me that all sorts of people were bothering her for interviews and that she had camera crews at her place following her around all the time. I told her I was interested in talking to her about what she's been up to recently and she asked bluntly, "How much time do you need?" I told her I didn't know, just a couple of hours, and then, in my usual tact, I said "I've not writing the book of your life, it's just a magazine article." She laughed at this and said she would give me two hours, "but no more!", and that I would have to come the next morning.

I called my editor and told him we had to move quickly and that this woman, Joan Hinton, was waiting for my call. We arranged to catch a cab together the next day, and I called Ms. Hinton back to let her know we would be there.

Gregoire and I, after some minor delay, made it to the farm WAY OUT in the countryside. Ms. Hinton brought out a notebook for us to sign--she keeps track of all her interviews--and she said, "So, what do you want to know."

For 85, Ms. Hinton is in pretty decent shape. She talks slowly, and her memory was perhaps not as sharp as it once was, but man, she flew across the room when the phone rang, or when she went to recover a piece of personal history to show me.

This woman came to China in 1948! She was a nuclear physicist with the Manhattan project, and after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, she left Los Alamos and tried to get the technology into civil hands. Of course, that failed. Then she came to China to join the communists! She married her husband, another American here, and had three children. They worked on dairies, and lived like everyone else.

Needless to say, interviews like this leave me a little starry-eyed. There are heaps more details to share, but I'm afraid that I'll have to leave them until after the magazine is published.

But wow. China is awesome.

But this interview was really something else. I don't think I can write terribly much about it here, as I am being paid to write about it for the magazine, but let me tell you just a bit about it. A friend of mine, while drunk at a party last year, told me about these Americans living on farm outside of Beijing who came to China to join the communist revolution. After many e-mails and phone calls, I found this woman. She was out in the city at a dinner event with Wen Jiabao when I called, but much to my surprise, she returned my call later that night. She asked me what I wanted and told me that all sorts of people were bothering her for interviews and that she had camera crews at her place following her around all the time. I told her I was interested in talking to her about what she's been up to recently and she asked bluntly, "How much time do you need?" I told her I didn't know, just a couple of hours, and then, in my usual tact, I said "I've not writing the book of your life, it's just a magazine article." She laughed at this and said she would give me two hours, "but no more!", and that I would have to come the next morning.

I called my editor and told him we had to move quickly and that this woman, Joan Hinton, was waiting for my call. We arranged to catch a cab together the next day, and I called Ms. Hinton back to let her know we would be there.

Gregoire and I, after some minor delay, made it to the farm WAY OUT in the countryside. Ms. Hinton brought out a notebook for us to sign--she keeps track of all her interviews--and she said, "So, what do you want to know."

For 85, Ms. Hinton is in pretty decent shape. She talks slowly, and her memory was perhaps not as sharp as it once was, but man, she flew across the room when the phone rang, or when she went to recover a piece of personal history to show me.

This woman came to China in 1948! She was a nuclear physicist with the Manhattan project, and after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, she left Los Alamos and tried to get the technology into civil hands. Of course, that failed. Then she came to China to join the communists! She married her husband, another American here, and had three children. They worked on dairies, and lived like everyone else.

Needless to say, interviews like this leave me a little starry-eyed. There are heaps more details to share, but I'm afraid that I'll have to leave them until after the magazine is published.

But wow. China is awesome.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Today is officially the second day of the October 1 holiday week. All of my students have cancelled on me, my school has closed (to be explained), IELTS will not be given until the weekend of the 14th, and while I still have writing work to do, all this has left me feeling exceptionally underwhelmed. I do now have an opportunity to put down a proper entry about what I've been up to, however.

The biggest news is that I've decided to put my masters on hold. I sent in the application for a one year's leave of absence last month, and while I have had word that it was received, I am awaiting final approval. Reasons for this decision were many, but the most salient was that I realized every spare second I had, along with every other spare penny I made, went into this program, and by the time I got to my year end finals (remember, this is a British course, so it all comes down to essays), I was really questioning whether or not it was worth it all in the end. I know this might sound like a weak attempt to cover up slack, or laziness on my part, but really, after a long think, a bit of screaming, and one moment of crying, I came to the conclusion that, while the material I was covering was highly engaging, two more years and another $8,000, might not bring me very much closer to my ultimate aims.

(And the crowds cry out, "Tell us, Maile! Tell us! What are those ultimate aims?!")

So like many a spoiled, middle-class, college educated, over-confident, under-skilled come recovering manic-depressive, yoga/insert your own brand of spirituality found brat, I, too, have wrestled with the great question of "What am I going to do with my life?!". This question, the quest for whose answer seems to best even the very best of us at around 24 or 25 (I believe someone who must have thought himself clever dubbed this ailment the "quarter-century crisis"), has consumed, or is presently consuming, most of the people I know in my age group, and even those older (they do say boys take longer to mature than girls). This affliction does seem to target a certain economic group (kids whose parents paid for their higher education), but culture offers no protection; I have met German, French, English, Chinese, Korean and Mexican sufferers.

Since I got out of school rather early--can you believe it's been more than 6 years already?!--I was fortunate to start this vicious process earlier, and as such, I am now sooner to feel its grip loosening. I concede, I'm not quite out of the woods completely, but I have found hope, and I do see light breaking through. Oddly enough, after all the agonizing, day dreaming, empire building and scrapping, soul-searching and expensive trips to the shrink, the elusive panacea we seem all struggle for, is actually something rather simple: just pick something. Pick something, something that hovers within the realm of reality, and then stick to it.

I want to be a journalist. Journalists are cool. They meet lots of interesting people, they get new things to do all the time and they work at different hours of the day, often in different places, and all of this appeals to me. What's more, I used to be a journalist, so I can with confidence say I know a bit about the work, and I know that I am competent enough to do it well enough to get paid for it. All of these are important considerations. The other thing I want to do is work in Asia. Lucky for me, I am already living here. (Actually, the desire came after the fact.) So, to put it succinctly, I want to be a journalist in Asia.

Once I made that decision, all the other decisions were easy to make. I started my masters (it is in Chinese business and international relations) because I felt it would give me the background necessary to look for jobs in journalism, here in China. (Research yielded that most of the journalism jobs in Asia are business and/or politics related.) I blew off my plans to go to France because I felt I could achieve more staying in here. I quit my regular job and found part-time work so I could focus on my ambitions. I also looked into getting internships, and here is where I found problems: 1. I was competing against recent journalism graduates who 2. maybe had better (foreign) language skills than me. Here was my dilemma. I was working so much that I didn't have time to study Chinese, and I didn't have time to write. I barely had time to sleep. So, I took the year off.

Very ironically, shortly after I quit my masters, my most generous employer, decided that my services were no longer needed. Ariston, the little boy I taught everyday for two hours, had reached the ripe old age of two and was good and ready for full-day kindergarten. To elaborate, what had happened was that a new brother came home, a cook got fired, the nanny took over all domestic duties, on top of managing the baby and the older brother who had a very serious case of sibling rivalry, Mom went back to work, so the tot was sent to school, and I was out of a cushy and reliable job.

There I was, no school, one job shy (I still had other students, plus the IELTS job, so I wasn't yet in a panic), and then something even more ironic, or rather fortuitous, happened: my pal Abel called me and offered me a job writing for a magazine. No shit.

Abel is one of the coolest people I have met in Beijing. At the tender age of 30, he's the bureau chief of Radio France International. He's been here years and years already, and he's very familiar with how the city works. One of his pals, Gregoire (these guys are all French, by the way) is the editor-in-chief of Colors Magazine (started by the Benetton people), and they were in need of writers for their upcoming issue profiling the issue.

Now, I'll tell you the difference between someone at the age of 20, and someone at the age of 26. At 20, you sincerely believe you'll make you're first million by 23, but if someone asks you to fax a document to a number in another city, and you don't already know how to do it, you panic, try to avoid the assignment, and then try to get someone else to do if for you. At 26, all you want is a job that doesn't suck too much, ideally one that has health benefits, and when someone offers you a job anywhere remotely in your area of interest, you say, in full confidence, "Yes. Yes. Gimme. Gimme. I can do it. No problem." Even if you know full well that you might not know exactly what you are doing, all of the silliness that you endure in your early 20s, assuming you overcome it, has the effect of making all obstacles look pretty similar, and eventually you realize, if you can conquer one, you can conquer them all.

So, I got the job. It's only a one-time, freelance gig, but I'm over the moon for it.

But let me tell you about French people. They are slow. I love them, but they are slow. Last summer, I worked with Germans, which was interesting. Germans are punctual to the point of absurdity ("OK, we will meet for breakfast at 9:32. Then we will start our meeting at 10:07"), but generally, their work practices are very compatible with Americans. French people, on the other hand, while very easy going, attentive, and passionate about their work, don't see the harm in having a cigarette and a cup of coffee before getting to an appointment. It's only life, after all.

When it comes to work, I am VERY American. Prolific communication is paramount, and I need to know what is happening at all times. If you tell me to call tomorrow, I will call tomorrow before noon. If I don't reach you, I will send an e-mail, and then call again before the day is out. Of course, I cut my teeth in the entertainment industry where everything is fast and one false step can get you fired, but I believe these are good work habits to have learned. If you're American, that is. French people are a bit different. Once they say they want you, that's it, they want you. But then you have to wait for their call. Or that how it seems to work, anyway.

Abel took more than a week to get back to me, and during that time, another funny thing happened. I was talking with an old colleague of mine who now is the director at the first school I taught at in Beijing. I mentioned that I was no longer teaching the two-year old, and I told him casually that if he ever needed someone to fill in if a teacher was ill, I'd be glad to do it. He called me the next day. Apparently, one of their teachers was very unhappy, so unhappy that she packed up her things and ran off like a thief in the night. She didn't tell her roommate, another teacher, about her plans. The next morning, the same morning they called me, they discovered what had happened when the roommate came to work and told them there wasn't a trace of the girl in the apartment. They asked me if I could come in to cover until a new teacher was produced, and I agreed to do so, on a part time basis, but at my current hourly rate, plus taxi fare (Ha! Ha! Ha! The power of scarce supply in high demand!)

So now, I'm back at Carden, teaching third grade (I must say, after two years, I'm much better at it), working for the magazine (they did call, but after a cigarette, or two), tutoring three students privately in the evenings, and working for the British Council on the weekends. I am thankful that I no longer have the demands of my masters course, and I am really quite impressed at how quickly I got busy, despite all the changes.

Dad once told me that he saw life as lugging around a sack. Throughout your life, you've got the same sack, and it's almost always full. Every time you think you've lightened your load by getting rid of something in the sack, you will inevitably quickly find something of equal mass to fill it up again. I don't know if this applies to all people, but I reckon I've inherited Dad's sack. It seems to be a big sack, and I seem to be forever yanking things out and stuffing in new ones, but at least it's quite clearly MY sack.

The biggest news is that I've decided to put my masters on hold. I sent in the application for a one year's leave of absence last month, and while I have had word that it was received, I am awaiting final approval. Reasons for this decision were many, but the most salient was that I realized every spare second I had, along with every other spare penny I made, went into this program, and by the time I got to my year end finals (remember, this is a British course, so it all comes down to essays), I was really questioning whether or not it was worth it all in the end. I know this might sound like a weak attempt to cover up slack, or laziness on my part, but really, after a long think, a bit of screaming, and one moment of crying, I came to the conclusion that, while the material I was covering was highly engaging, two more years and another $8,000, might not bring me very much closer to my ultimate aims.

(And the crowds cry out, "Tell us, Maile! Tell us! What are those ultimate aims?!")

So like many a spoiled, middle-class, college educated, over-confident, under-skilled come recovering manic-depressive, yoga/insert your own brand of spirituality found brat, I, too, have wrestled with the great question of "What am I going to do with my life?!". This question, the quest for whose answer seems to best even the very best of us at around 24 or 25 (I believe someone who must have thought himself clever dubbed this ailment the "quarter-century crisis"), has consumed, or is presently consuming, most of the people I know in my age group, and even those older (they do say boys take longer to mature than girls). This affliction does seem to target a certain economic group (kids whose parents paid for their higher education), but culture offers no protection; I have met German, French, English, Chinese, Korean and Mexican sufferers.

Since I got out of school rather early--can you believe it's been more than 6 years already?!--I was fortunate to start this vicious process earlier, and as such, I am now sooner to feel its grip loosening. I concede, I'm not quite out of the woods completely, but I have found hope, and I do see light breaking through. Oddly enough, after all the agonizing, day dreaming, empire building and scrapping, soul-searching and expensive trips to the shrink, the elusive panacea we seem all struggle for, is actually something rather simple: just pick something. Pick something, something that hovers within the realm of reality, and then stick to it.

I want to be a journalist. Journalists are cool. They meet lots of interesting people, they get new things to do all the time and they work at different hours of the day, often in different places, and all of this appeals to me. What's more, I used to be a journalist, so I can with confidence say I know a bit about the work, and I know that I am competent enough to do it well enough to get paid for it. All of these are important considerations. The other thing I want to do is work in Asia. Lucky for me, I am already living here. (Actually, the desire came after the fact.) So, to put it succinctly, I want to be a journalist in Asia.

Once I made that decision, all the other decisions were easy to make. I started my masters (it is in Chinese business and international relations) because I felt it would give me the background necessary to look for jobs in journalism, here in China. (Research yielded that most of the journalism jobs in Asia are business and/or politics related.) I blew off my plans to go to France because I felt I could achieve more staying in here. I quit my regular job and found part-time work so I could focus on my ambitions. I also looked into getting internships, and here is where I found problems: 1. I was competing against recent journalism graduates who 2. maybe had better (foreign) language skills than me. Here was my dilemma. I was working so much that I didn't have time to study Chinese, and I didn't have time to write. I barely had time to sleep. So, I took the year off.

Very ironically, shortly after I quit my masters, my most generous employer, decided that my services were no longer needed. Ariston, the little boy I taught everyday for two hours, had reached the ripe old age of two and was good and ready for full-day kindergarten. To elaborate, what had happened was that a new brother came home, a cook got fired, the nanny took over all domestic duties, on top of managing the baby and the older brother who had a very serious case of sibling rivalry, Mom went back to work, so the tot was sent to school, and I was out of a cushy and reliable job.

There I was, no school, one job shy (I still had other students, plus the IELTS job, so I wasn't yet in a panic), and then something even more ironic, or rather fortuitous, happened: my pal Abel called me and offered me a job writing for a magazine. No shit.

Abel is one of the coolest people I have met in Beijing. At the tender age of 30, he's the bureau chief of Radio France International. He's been here years and years already, and he's very familiar with how the city works. One of his pals, Gregoire (these guys are all French, by the way) is the editor-in-chief of Colors Magazine (started by the Benetton people), and they were in need of writers for their upcoming issue profiling the issue.

Now, I'll tell you the difference between someone at the age of 20, and someone at the age of 26. At 20, you sincerely believe you'll make you're first million by 23, but if someone asks you to fax a document to a number in another city, and you don't already know how to do it, you panic, try to avoid the assignment, and then try to get someone else to do if for you. At 26, all you want is a job that doesn't suck too much, ideally one that has health benefits, and when someone offers you a job anywhere remotely in your area of interest, you say, in full confidence, "Yes. Yes. Gimme. Gimme. I can do it. No problem." Even if you know full well that you might not know exactly what you are doing, all of the silliness that you endure in your early 20s, assuming you overcome it, has the effect of making all obstacles look pretty similar, and eventually you realize, if you can conquer one, you can conquer them all.

So, I got the job. It's only a one-time, freelance gig, but I'm over the moon for it.

But let me tell you about French people. They are slow. I love them, but they are slow. Last summer, I worked with Germans, which was interesting. Germans are punctual to the point of absurdity ("OK, we will meet for breakfast at 9:32. Then we will start our meeting at 10:07"), but generally, their work practices are very compatible with Americans. French people, on the other hand, while very easy going, attentive, and passionate about their work, don't see the harm in having a cigarette and a cup of coffee before getting to an appointment. It's only life, after all.

When it comes to work, I am VERY American. Prolific communication is paramount, and I need to know what is happening at all times. If you tell me to call tomorrow, I will call tomorrow before noon. If I don't reach you, I will send an e-mail, and then call again before the day is out. Of course, I cut my teeth in the entertainment industry where everything is fast and one false step can get you fired, but I believe these are good work habits to have learned. If you're American, that is. French people are a bit different. Once they say they want you, that's it, they want you. But then you have to wait for their call. Or that how it seems to work, anyway.

Abel took more than a week to get back to me, and during that time, another funny thing happened. I was talking with an old colleague of mine who now is the director at the first school I taught at in Beijing. I mentioned that I was no longer teaching the two-year old, and I told him casually that if he ever needed someone to fill in if a teacher was ill, I'd be glad to do it. He called me the next day. Apparently, one of their teachers was very unhappy, so unhappy that she packed up her things and ran off like a thief in the night. She didn't tell her roommate, another teacher, about her plans. The next morning, the same morning they called me, they discovered what had happened when the roommate came to work and told them there wasn't a trace of the girl in the apartment. They asked me if I could come in to cover until a new teacher was produced, and I agreed to do so, on a part time basis, but at my current hourly rate, plus taxi fare (Ha! Ha! Ha! The power of scarce supply in high demand!)

So now, I'm back at Carden, teaching third grade (I must say, after two years, I'm much better at it), working for the magazine (they did call, but after a cigarette, or two), tutoring three students privately in the evenings, and working for the British Council on the weekends. I am thankful that I no longer have the demands of my masters course, and I am really quite impressed at how quickly I got busy, despite all the changes.

Dad once told me that he saw life as lugging around a sack. Throughout your life, you've got the same sack, and it's almost always full. Every time you think you've lightened your load by getting rid of something in the sack, you will inevitably quickly find something of equal mass to fill it up again. I don't know if this applies to all people, but I reckon I've inherited Dad's sack. It seems to be a big sack, and I seem to be forever yanking things out and stuffing in new ones, but at least it's quite clearly MY sack.

Thursday, September 28, 2006

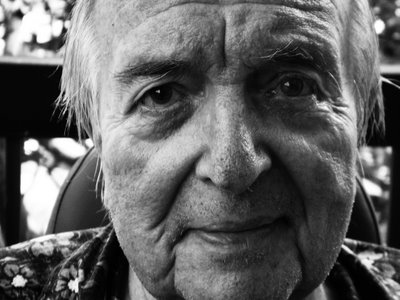

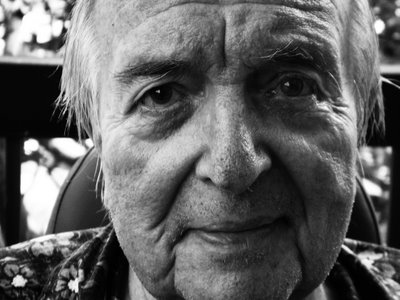

My dad's birthday was yesterday (in the States; it was two days ago on Chinese time), and he turned 82! (I can hear the collective gasp, "82?! Christ that's old!" And as my dad would, and did, say, "Christ, that IS old!"

My dad's an interesting cat, and he runs with an interesting crowd. Most of his friends are dirty, old men. Brilliant, dirty, old men, but dirty, old men, nonetheless. One of my dad's oldest and greatest friends is a guy called Sandy Singleton (really, that's his name). I have known Sandy since I can remember, and he's known Dad longer than I have, by a lot. Sandy also has a daughter who is either two weeks older, or younger than me (I can't remember).

Sandy has always been a controversial figure in my family. My mother hates him with a venomous pith, and for a very long time, he was banned from the house. When he would call, just looking for Dad, my mother would hang up on him. I am not sure about all the details that explain my mother's reaction to this guy--I can only assume that a good number of them lie within her own unreasonableness and extremist behavior--but I can tell you this: My mother and Sandy have a hell of a lot in common. Both are impulsive and self-righteous, and both are aggressive self-promoters. They are both sharp as tacks, but both also suffer from a similar physiological ailment: The wire that connects the brain to the mouth and prevents people from saying inappropriate things at inappropriate times has been irrevocably severed.

My mother has been known to comment on how ugly someone's baby is, within earshot of the parents, and she has never been shy about expressing her great disdain for Mormons. Sandy, likewise, finds intolerance for certain sections of humanity. Fat people, for instance, especially suffer under his scrutiny. (Sandy believes that all fat people should be rounded up and sent to labor camps until they work off their excess adipose and have body shapes more to his liking.) My mother's name for Sandy during my growing up years, was "Monkey" or "Swingleton", and Sandy found such choice ways to describe my mother, beyond the most obvious "Dragon Lady", as "Maoist nazi."

Since my parents divorced, Sandy has reentered my father's life and, indirectly mine. Having already found great patience for my own mother's strange behavior, I find Sandy to be generally interesting, if not at least, amusing. Sandy is actually quite a brilliant guy with a very active mind, and imagination. While I was last living in Hawaii, he would buy the New York Times Sunday edition every week, as well as the Economist, and then he would pass them both to Dad and me, for a read. And despite everything, Sandy has been an excellent friend to my dad. When Dad had his stroke and broke his hip, Sandy helped him get around Honolulu, in the hospitals and airports. And, to this day, he is one of the few to brutally remind my father that he shouldn't eat shit like danish donuts, and that despite his predicament, he should make some attempt at exercise.

So the other day, I got an e-mail from Sandy, a rare occurrence, indeed. This is what it was:

I asked this learned type lady I met at Starbucks if she thought all the world's problems were caused by ignorance and apathy.

She told me that not only did she not know, but that she didn't give a shit.

I told Cannon. He could not stop laughing. He called two days later and said he keeps thinking about it and can't stop chortling, or something akin to laughing, again.

(I think the actual actual answer was: I don't know, and I don't care. I like to add my street wit to things.)

In any event, this is the first time I have ever come up w/ something to tell Cannon he did not already know. It has made my year... Ah, such simple things can bring such inner peace...

I told Dad that Sandy e-mailed me this, and he was amused. At his age, Pop should know that it's the simple stuff that keeps you going.

Here's a picture of the old man. It was taken on the last trip to Hawaii, but I doctored it up to look artsy and pretentious. Once Dad writes the book of his life, we will use for the jacket cover.

My dad's an interesting cat, and he runs with an interesting crowd. Most of his friends are dirty, old men. Brilliant, dirty, old men, but dirty, old men, nonetheless. One of my dad's oldest and greatest friends is a guy called Sandy Singleton (really, that's his name). I have known Sandy since I can remember, and he's known Dad longer than I have, by a lot. Sandy also has a daughter who is either two weeks older, or younger than me (I can't remember).

Sandy has always been a controversial figure in my family. My mother hates him with a venomous pith, and for a very long time, he was banned from the house. When he would call, just looking for Dad, my mother would hang up on him. I am not sure about all the details that explain my mother's reaction to this guy--I can only assume that a good number of them lie within her own unreasonableness and extremist behavior--but I can tell you this: My mother and Sandy have a hell of a lot in common. Both are impulsive and self-righteous, and both are aggressive self-promoters. They are both sharp as tacks, but both also suffer from a similar physiological ailment: The wire that connects the brain to the mouth and prevents people from saying inappropriate things at inappropriate times has been irrevocably severed.

My mother has been known to comment on how ugly someone's baby is, within earshot of the parents, and she has never been shy about expressing her great disdain for Mormons. Sandy, likewise, finds intolerance for certain sections of humanity. Fat people, for instance, especially suffer under his scrutiny. (Sandy believes that all fat people should be rounded up and sent to labor camps until they work off their excess adipose and have body shapes more to his liking.) My mother's name for Sandy during my growing up years, was "Monkey" or "Swingleton", and Sandy found such choice ways to describe my mother, beyond the most obvious "Dragon Lady", as "Maoist nazi."

Since my parents divorced, Sandy has reentered my father's life and, indirectly mine. Having already found great patience for my own mother's strange behavior, I find Sandy to be generally interesting, if not at least, amusing. Sandy is actually quite a brilliant guy with a very active mind, and imagination. While I was last living in Hawaii, he would buy the New York Times Sunday edition every week, as well as the Economist, and then he would pass them both to Dad and me, for a read. And despite everything, Sandy has been an excellent friend to my dad. When Dad had his stroke and broke his hip, Sandy helped him get around Honolulu, in the hospitals and airports. And, to this day, he is one of the few to brutally remind my father that he shouldn't eat shit like danish donuts, and that despite his predicament, he should make some attempt at exercise.

So the other day, I got an e-mail from Sandy, a rare occurrence, indeed. This is what it was:

I asked this learned type lady I met at Starbucks if she thought all the world's problems were caused by ignorance and apathy.

She told me that not only did she not know, but that she didn't give a shit.

I told Cannon. He could not stop laughing. He called two days later and said he keeps thinking about it and can't stop chortling, or something akin to laughing, again.

(I think the actual actual answer was: I don't know, and I don't care. I like to add my street wit to things.)

In any event, this is the first time I have ever come up w/ something to tell Cannon he did not already know. It has made my year... Ah, such simple things can bring such inner peace...

I told Dad that Sandy e-mailed me this, and he was amused. At his age, Pop should know that it's the simple stuff that keeps you going.

Here's a picture of the old man. It was taken on the last trip to Hawaii, but I doctored it up to look artsy and pretentious. Once Dad writes the book of his life, we will use for the jacket cover.

Friday, September 22, 2006

For all intents and purposes, I speak Chinese. It's not pretty, it's rarely accurate and it often requires elaboration with hand gestures and sound effects--but I speak it, and more often than not, I get my point across.

However, after two and a half years in this mad place, I have learned that there are two places where I should never ever try to impress anyone with my rudimentary grasp of the Mandarin language: airports and police stations.

With my new job, I fly a lot, so I'm always in and out of airports. If you speak Chinese, especially if you've got a face like mine, you are simply subject to more rules, regulations and inspection. My asthma inhaler always raises questions at security, and I have found, that instead of trying to explain what it is, it is far easier just to ramble away quickly in English. Nine times out of ten, the English of the person on the receiving end is far too limited to understand any explanation employing higher level medical terminology, and they know this, so rather than even making an attempt to interrogate me, they just wave me through.

Police stations, in any country, can be intimidating, and I think in China, they are more so. But police stations here are everywhere, and they are very much an integral part of Chinese life. Beyond maintaining law and order, police here get involved in people's daily lives. All residents, including foreigners, must register with the local police station when moving house. Police stations manage the distribution of identity cards, and children, once born, must also have a record on file with the police.

Today, I went to my local branch of the Public Safety Bureau to reregister after getting a new visa. The last time I did it, it was a snap, and everyone at the station was very happy to chat with the new American girl who looks Chinese, but can't speak the language very well. (But they did tell me that I spoke well enough to be understood, and that with time I would improve.)

This time around however, it was a completely different story. The woman beyond the counter, in a stiff blue blouse with navy epaulettes, her long black hair pulled back from her small, clean face meticulously, refused to register me. She explained, with the help from a guy in the queue that I had violated a regulation requiring foreigners to register within 24 hours of arrival.

Bullshit.

It was at least a month between the time I moved into my new place and the time I actually made my way down to the police station to formalize everything. What the hell was this woman going on about?

She then grilled me as to why I had taken nearly three weeks since the renewal of my visa to come into the station. The truth of it was 1. I'm a busy kid. I travel all over hell and gone, and when I'm in town, my time is usually stretched to the limit, and 2. I didn't think it was that big of a deal.

"Wo you shi," I said. It's the Chinese catch all phrase for, "I was busy. I was too lazy. I didn't feel like it..." It works in every situation, and no matter what the truth is, no one will question it. Except at the police station.

Madame Civil Servant, with her small lips painted carefully with red lipstick, told me that since I hadn't come in time, I would have to go to the district station, which was located somewhere deep in the hutong.

Fuck.

So off I went in a cab, meandering along the small alleyways of the old part of town in search of my Public Safety fate.

But this time, I got smart.

"Where do I register?" I asked the guard who looked as though his grasp of Mandarin may have been questionable, let alone his familiarity with English.

"She's a foreigner!" he yelled to his colleagues.

So at the gate I waited until they produced someone who could speak English. A guy came out, told me I did something wrong, I apologized like a bumbling foreign idiot, and then he went, with all my documents, back into the massive district office. He came back about fifteen minutes later with a handwritten piece of paper and said, "Sign this."

"What is it?" I asked, like every good American girl born to a lawyer father. He gave me a slightly irritated "how-dare-you-ask" look, but then said, "It's a warning!"

I signed it, apologized profusely, promised never to be so negligent again, and then made my way back to the first place. On the way, I stopped for a sesame bun from a street vendor, and we chatted a bit about why I look Chinese, but speak Chinese with an accent.

Back at the station, the Heavy Hand of Bureaucracy had been replaced by a very pleasant middle-aged woman. I handed her all of my papers, and made no mention of my written warning. She processed everything quickly, and with a smile, and asked me some basic questions about where I was from. Very much to my surprise, she gave me my registation form, valid for the year, and made no reference to the discrepancy between today's date, and the one found on my visa, and then sent me on my way.

If only I had come later in the day, in the first place! That's local bureaucracy for you! Man, you win some and you lose some.

However, after two and a half years in this mad place, I have learned that there are two places where I should never ever try to impress anyone with my rudimentary grasp of the Mandarin language: airports and police stations.

With my new job, I fly a lot, so I'm always in and out of airports. If you speak Chinese, especially if you've got a face like mine, you are simply subject to more rules, regulations and inspection. My asthma inhaler always raises questions at security, and I have found, that instead of trying to explain what it is, it is far easier just to ramble away quickly in English. Nine times out of ten, the English of the person on the receiving end is far too limited to understand any explanation employing higher level medical terminology, and they know this, so rather than even making an attempt to interrogate me, they just wave me through.

Police stations, in any country, can be intimidating, and I think in China, they are more so. But police stations here are everywhere, and they are very much an integral part of Chinese life. Beyond maintaining law and order, police here get involved in people's daily lives. All residents, including foreigners, must register with the local police station when moving house. Police stations manage the distribution of identity cards, and children, once born, must also have a record on file with the police.

Today, I went to my local branch of the Public Safety Bureau to reregister after getting a new visa. The last time I did it, it was a snap, and everyone at the station was very happy to chat with the new American girl who looks Chinese, but can't speak the language very well. (But they did tell me that I spoke well enough to be understood, and that with time I would improve.)

This time around however, it was a completely different story. The woman beyond the counter, in a stiff blue blouse with navy epaulettes, her long black hair pulled back from her small, clean face meticulously, refused to register me. She explained, with the help from a guy in the queue that I had violated a regulation requiring foreigners to register within 24 hours of arrival.

Bullshit.

It was at least a month between the time I moved into my new place and the time I actually made my way down to the police station to formalize everything. What the hell was this woman going on about?